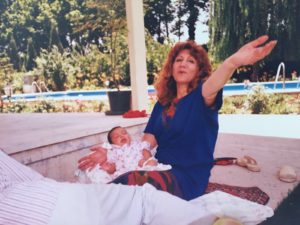

The author and her grandmother, taken at the family country home in Karaj, Iran. Photo: Roya Dehghani.

Mur-ab-ba, Farsi for “jam,” is one word, three syllables. My grasp of Farsi is limited at best, and there are words that I struggle to recall in conversation, as they skirt the edge of my memory and get trapped on the tip of my tongue. But murabba has never been one of those words.

Twelve years old and seated on the Persian rug in my grandparents’ living room, I’m surrounded by newspapers in a language I can’t read—and by a mountain of fresh blackberries scattered across them. Maman Mahin, my grandmother, is seated cross-legged next to me, scrutinizing each berry. Only the best, sweetest berries will be used to make her jam. I mimic her, in truth eating a lot more blackberries than I’m inspecting. We could be anywhere, but for the din of Tehran traffic coming in from the window and the Farsi-speaking news anchors my grandfather attentively watches on the TV.

My mother has sent me to Tehran for the summer, to better understand my roots and spend time with the Iranian side of my family. For three months I wake up each morning excited, not because of whatever cultural activities my grandma has planned for us, but for breakfast. It’s a spread of fresh bread from the bakery, Iranian cheese, mint leaves, walnuts, butter, and jam, a variation of the breakfasts my mom would occasionally prepare for us back home in Canada. Of course, this is the real thing, made from ingredients in our backyard (literally and figuratively), not imports from overpriced Iranian grocery stores in Toronto.

Amidst all the colorful, fragrant, uniquely delicious Persian cuisine I’ve been raised on, what stands out the most in my memory is my grandmother’s jam. It has just two ingredients: fruit and sugar, not unlike the ingredient list of a jar of farmer’s market preserves. Yet Maman Mahin’s murabba tastes nothing like those jars, at least not to me.

Her jam is an art no one in my family can re-create perfectly. Fruit stewed in sugar becomes chunks of whole strawberries, quince, or orange blossom, floating in a syrupy reduction. It tastes like childhood, of lazy weekend mornings in Toronto or summers spent in Iran, slathering a completely imbalanced jam-to-butter ratio on whole-wheat pitas, the strawberries inevitably falling off the bread.

Our fridge in Canada is never without a jar, as Maman Mahin smuggles suitcases full of the stuff every time she visits our family there. She always makes sure to give us extra jars of tootfarangi jam, strawberry, not particularly exotic, but my brother and my favorite. Each family member has their own preference: beh (quince), gilas (sour cherry), albaloo (cherry), bahare naranj (orange blossom), the list goes on.

The author’s grandparents and their five children on a family vacation in Iran. Photo: Roya Dehghani.

Filled with fruit from the gardens of the family country home in Karaj, an hour car ride from Tehran, the jam is my mother’s teenhood. On four acres of land, with a house in the center and a pool out front, sit the pear trees my great-grandma planted, the sour cherry trees my aunts plucked fruit from, and the walnut trees that supplied their breakfast staple.

When my mom and her siblings eventually left Iran for India, America, Germany, and Canada, the jam followed, well-traveled, packed with extra care in suitcases so the glass jars wouldn’t shatter. For my mom, 17 years old and studying medicine in India, her first time away from her parents for an extended period of time, each spoonful of Maman Mahin’s jam was home.

Though four of their five children live abroad now, my grandparents still reside in the same apartment building in Tehran I grew up visiting. I don’t see them as much as I’d like, and the last time I saw Maman Mahin in person was a couple years ago when she visited Canada. There are moments where I feel guilty for not having gone to visit them in Iran since I was in grade school, but something always came up, whether it was jobs or summer courses. Those moments are often coupled with pangs of nostalgia, missing my grandparents and other relatives in Iran, a place I feel more disconnected from, after all the years I’ve been away.

It’s in those moments that I reach for the large glass jar in the back of my fridge. I twist off the stubborn gold-colored lid, its sides sticky with deep red syrup, and spread a spoonful of the strawberry murabba on a piece of bread with butter. When I take a bite, I’m twelve years old again and back on my grandparents’ living room floor. I still can’t read the Persian newspaper, and only understand sixty percent of what the TV newscaster is saying. But seated next to my grandma, it doesn’t really matter. We continue inspecting berries.

Tags: Breakfast, fruit, immigration, iran, jam

Your Comments