In the hour before dawn, the kitchen light glowed like a beacon in the dark. To reach it, my little feet had to pad across a hallway lined with 64 small picture windows that looked out into the humid, Malaysian night. Ten-year-old me did not dare glance at the uncovered glass, because my brothers said that if I stared into the blackness long enough, I would see a woman in white staring back.

But a part of me knew that this month, the ghosts would stay away. It was the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, and God had locked the gates of hell to keep the spirits in. I could make my way towards the pre-dawn meal – which we call Sahur – without feeling afraid in my own house, as I often did in the dark.

I sat down at the kitchen table with the heaviness that comes from being uprooted from a dream, which was often the case at about 5 a.m. My father was already sitting at the head of the table, and my three older brothers were scattered around. My younger sister, only two at the time, would be fast asleep in my parents’ bed. My mother’s small frame fluttered around the room, heating up dishes to set in front of her family. My grandmother, who didn’t yet need two titanium kneecaps, helped her.

There are two main reasons why this scene, of a little girl and her family about to eat together, with the sound of early morning birdsong playing in the back, is so important to me.

The first is that it was a religious act, and at that age, with four hours of Islamic lessons a week, I was very afraid of God. Sahur is the pre-dawn meal during Ramadan, the ninth month in the Islamic calendar, when Muslims are supposed to fast from sunrise to sunset. No food, no drink. Not even water. Sahur was supposed to sustain you for the rest of the day. At ten years old, I had only just begun completing full days of fasting, which I considered a triumph in 95-degree Malaysia. Otherwise, I would muster half a day, which I had started the year before, and break my fast after lunch. No matter the outcome, taking Sahur remained constant. It was the ritual I could dutifully carry out, eating and drinking so I could later abstain from them both, in order to please the creator of the universe.

The second reason I treasure this memory is because it was the only time the members of my family ate together when I was a child. The way I saw families share meals on American television shows – the mother calling the kids down for breakfast, the dad asking you to pass the bread at dinner – was not a part of my childhood reality. It’s not that each person always ate alone, but that it was just incredibly rare for everyone to eat at the same time and in the same place. My father was often busy with work, my teenage brothers were either with friends or being angsty in their rooms, and I preferred eating with my nose in a book, which didn’t lend itself to convivial dinnertime conversation.

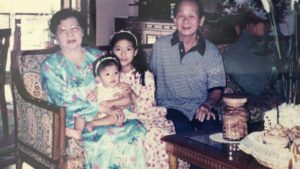

My little sister and I during Eid with both our Chinese grandparents; grandma converted to Islam, while grandpa remained a Taoist. Photo: Aisha Hassan.

But at 5 in the morning, everyone was home. My mother said to me recently that we used to eat Sahur with our eyes half closed, but I can still see it all with an aching clarity, though my nose and taste buds probably helped. Even though the selection of dishes varied throughout the month, there would always be nasi goreng, or fried rice in Malay, cooked kampung or “village”-style with anchovies, long beans, and water spinach, and congee, a simple rice porridge topped with chopped peanuts and anchovies and sprinkled with soy sauce. My mother is Chinese and my father is Malay, so the combination seemed only natural. After eating Sahur, it was a comfort to know everyone was also fasting together. By the time sunset came and the call to prayer let us take a small sip of water and a bite of a medjool date, there was usually someone missing.

That year, 2004, was the last time my family lived together in the same house. My eldest brother left for university in England, followed by the second, and by the time my third brother left and the eldest was returning, I had flown off to boarding school. My little sister will leave for Europe for school this year, my brothers are scattered across Asia, and I now live in New York. It is a rarity for my family to be together in the same continent, let alone the same kitchen.

When Ramadan rolls around each year, I wish that I was home. I never fast outside of Malaysia. The days are usually too long, and fasting is something so deeply entrenched with my experience of home that it feels strange to do it anywhere else. I am also a little less afraid of God.

On the handful of times I’ve had Sahur in Malaysia since leaving home at 16, there have always been empty seats at the table. They fill out haphazardly throughout the year, when each of my siblings and I fly by. Sahur has become emblematic of family for me in a way that no meal has ever since, but it is no longer my only emblem of family. I am closer to them than I have ever felt before, even from the other side of the world.

Your Comments