Reading beyond the recipe

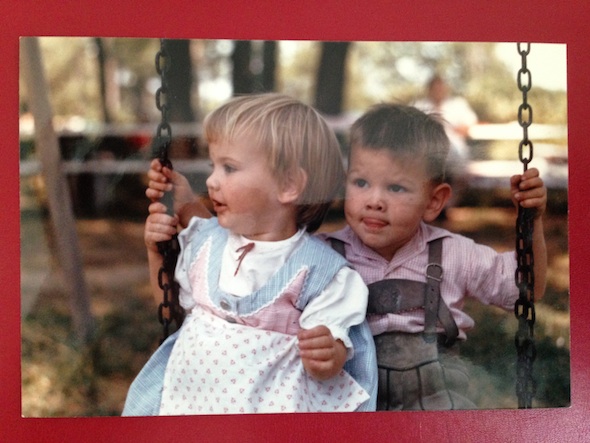

Cassandra Basler’s aunt and father dressed in traditional dirndl and lederhosen before an outdoor feast at the Austrian Society of Detroit (1964).

Gundel’s Hungarian Cookbook says every good dish starts with two essentials: brown onion and paprika. Since my family’s Austrian, we’d say every good dish starts with brown onion and garlic. But there’s a favorite of my grandmother’s that combines these—chicken paprikash.

When I was growing up, fall wouldn’t officially arrive until those slow-cooked chicken legs began to simmer in a 12-quart steel stockpot on my Omi’s stove. The best part—the sauce—matched the rust-colored leaves outside my grandparents’ kitchen window, just north of Detroit.

Omi cooked the paprikash days before our Sunday dinner, but a half hour before my family arrived, she’d heat the pot on low. That way, the earthy aroma would still waft from her freshly-scrubbed kitchen. My Opi would say, “I hope you came hungry, Omi’s been cooking all week!” And Omi would laugh as though the hardest part was pulling the heavy cookware from the highest cabinet. (Omi only stood about five feet tall.)

During my junior year in college, I decided to cook paprikash for my German Club potluck. I never knew what went into that favorite sauce, because I’d never watched Omi stir the onions and minced garlic until it cooked down into a terracotta red. I just wolfed it down when she ladled it onto a bed of freshly boiled dumplings, lightly coated with butter. But I had to prove to the Germanophiles that Austrian food outshined the bratwurst we’d wash down with Weissbier at the Heidelberg pub downtown.

I just couldn’t find the right recipe.

Plenty of Americanized iterations popped up on Google. Slow-cooker recipes for Weight Watchers, ladled over half-cup helpings of wide Scandinavian egg noodles. “Mozart Paprikash,” a chunky grey-white atrocity served with green bell peppers and paprika as a garnish. My dad’s own version came sprinkled with northern Italian herb seasoning and served with store-bought German spätzle noodles. Few recipes featured my Omi’s hand-pinched nockerln, the tiny egg and flour dumplings the size of your fingertip.

So, on January 21st, 2011, I emailed my dad for help. With my Omi and the rest of my immediate family carbon-copied, he sent ingredients and a full block of instructions. One step wasn’t separated from the one before it. Omi replied as well, to my relief, but this was her only comment:

“follow your Dad’s recipe and put Paprika in stir and add tomato paste otherwise it turns bitter. I don’t add Italian spices and just use a little ground nutmeg and a tiny bit of lemon. It’s easier to just reheat the next day and add sour cream after you turn off burner.”

I figured even if I couldn’t master Oma’s Viennese dialect, I could break down this recipe and cook a decent paprikash. As a second generation Austrian, I’d struggled to understand a language and a culture my grandparents tried to clear from every room of their lives—except the kitchen. But in the tiny attic flat that was my first apartment, my kitchen was just an afterthought, something the couch backed up to.

Still, once I found paprika at the local supermarket—not the familiar red, green and white Hungarian tin that sat in my kitchen cabinet growing up, but some faded red powder in a glass bottle—I skinned and sliced chicken thighs on a sliver of Formica countertop. Then I splattered two minced garlic cloves and yellow onions into hot olive oil, which burned my arm and coated my wall. My shallow pasta pot was not made to handle this meal. I didn’t have fresh nutmeg—or even a nut grinder—so I settled for a sprinkle from our baking supplies. My roommate helped me stir in the paprika-coated meat, chicken stock and a dollop of tomato paste. At that point, I decided those store-bought spätzle noodles would do, because I couldn’t handle two extra hours of pinching dough into little nockerln. Finally, the sizzling mess cooked down into a dark red stew—a bit deeper than the dish I was used to, even after I mixed in a dollop of sour cream before serving.

Mine probably wasn’t the worst paprikash in history. The German Club certainly didn’t know the difference. But the tricky thing about chicken paprikash is that it’s the essence of Budapest, the city taken over by the Austrian Hapsburgs and molded into the “Vienna of the East.” It’s difficult to claim as my favorite Austrian meal, because it’s sort of an appropriated dish. A product of several cultures, like my Viennese grandparents and my American dad.

Maybe that’s why I like paprikash so much. No ingredient seems too distinct, once it’s on the table.

Tags: austrian, chicken paprikash, garlic, hungarian, onion, paprika

Your Comments