My three cousins and I raced into the house, my mother’s childhood home in Morelos, Mexico, giggling wildly as our leather flip flops slapped the pavement, scorching hot under the July sun. Our parents herded us out of the backyard so that we didn’t witness our abuelita, my maternal grandmother, slaughter the chickens. I had to settle for my father’s description of her method – which he, an American, first saw after marrying my mother. She placed her thumb at the base of the skull and popped the head from the neck like a bottle cap. She was a master of the art, sometimes killing two at a time.

The four of us flung ourselves on the couch and sat in a line facing backward with our knees digging into the cushions. We peered out the window into the immense yard that housed my abuelita’s livestock and her garden that teemed with twisting vines, gnarled trees, cacti of all shapes and sizes and delicate flowers. To this day the night-blooming saguaro cacti that loom over the house feed the long-nosed bats. Moments later she appeared with two limp chickens dangling upside down from her fist. A cloud of steam billowed out from her pot of boiling water and aromatics in the yard, all but obscuring her from sight. She looked like a sorceress in her long blue dress; I watched as she ripped out fistfuls of feathers that fell at her feet like petals. The carnage looked like magic to me when I was six.

The plucked chickens went into the pot and emerged an hour later ready to eat. That night the family sat scattered around the house as the dining room could not hold all of us. I sat on the edge of the bed where I was staying with my parents and sucked the warm liquid that burst from each bite. “Mommy,” I said. “Abuelita’s chicken has water in it.”

“It’s not water, it’s juicy,” my mom answered. The fatty liquid stuck to my face.

These were the last two chickens she ever kept. Abuelita died two years later, having said many times in her final years that she wanted to return to my abuelito, my mother’s father, who died when I was a few months old.

Throughout her adult life my abuelita kept a menagerie of animals. She was a schoolteacher who met my abuelito while doing her fieldwork requirement. During the day she taught the children of his rural town how to read and by night she taught the adults. She first bought chickens so that my tios, my uncles, would have responsibilities to come home to after school as a way to keep them out of trouble. Selling them and having fresh meat was just a bonus. Her sister gave her two rabbits, which multiplied to 50, and she sold them live to restaurants little by little until one day a buyer bought the last 30. Countless doves lived in a coop she kept on the roof. She had a number of other animals: a parrot, a turkey and a turtle the boys caught in the river. Only the doves were left when she died. When the last one passed her garden fell silent. My tia Ney, the second-oldest child, still owns the house.

Hearing of her death was confusing for me. I lived in the U.S. and was often removed from the realities my mother’s family in Mexico was facing. Even now I can recall the sadness everyone felt after her death, but I can’t feel it. It is a distant emotional pang that I can’t make sense of. That feeling of insuperable separation haunts me even now as I try to put together my brief list of memories of her. The roots of my family tree are built around someone I can never reach.

We try to recreate her recipes, though everyone remembers them differently. One relative might say they know best because they went with her to the store to buy the ingredients. Another might say it’s their absolute favorite dish, so of course they know it best. Another says they were standing at her knee in the kitchen when she made it. The details are sometimes hotly contested. I have a vivid memory of my mother cutting through the competing voices saying “Ay callate” (Oh, shut up) to my tia Geno, her sister, who had embellished a story.

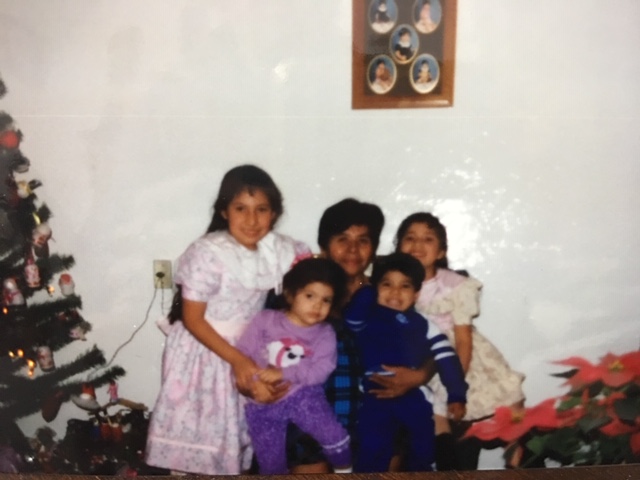

But as absurd as it sounds, we were fortunate. My abuelita valued our presence in her kitchen, crowding all eight of her children, their spouses and their children into her kitchen whenever my parents and I visited, even if some had to sit on the staircase.

For a few days after my abuelita slaughtered the chickens my cousins and I went out back hoping to chase them, unable to comprehend the permanence of death. More than 20 years later and I seek my abuelita every time I return to Mexico, hoping this time I might find her.

Tags: chicken, Family, Mexican food

Your Comments