When Ketrina Hazell needs a glass from the kitchen cabinet, it’s a complicated task. First, she steers her wheelchair up to the counter. Then, she leans her right hand on the chair, hoisting herself closer to the shelf. She tries to snatch the glass safely from the shelf without losing her balance. One mistake, and a dropped glass could shatter and injure the 24-year-old Hazell.

“It’s something I’m always in fear of,” says Hazell, who has cerebral palsy and has been in a wheelchair her whole life, with limited use of her left hand. Like many of the 60,000 wheelchair users who live in New York City, Hazell faces challenges using the kitchen.

For most New Yorkers, wide door frames, spacious kitchens and easy-to-reach electrical outlets are amenities that improve their quality of life. For people in wheelchairs, those features could determine whether they’re able to cook their own meals.

Monica Bartley, 62, worked with a broker to find her apartment in Bushwick with a wheelchair-friendly design. “There are grab bars in the bathroom and the doorways are wide enough so I didn’t have a problem maneuvering the wheelchair,” she explained.

Since 1988, all new NYC housing developments built using any federal funding must have at least 5 percent of units accessible for people with impaired mobility. Such apartments must include features like wider doors and light switches placed within reach of someone using a wheelchair. Building codes established in 2008 and 2014 also require all buildings in the city to feature adaptable units, according to Arthur Jacobs, housing coordinator for the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities.

But finding an available apartment can be challenging, according to disability advocates like Shameka Andrews of the Self Advocacy Association of New York State. “In my work, I’ve seen that there aren’t a lot of accessible apartments,” she said. “Most people have to live with whatever they can find.”

Until December, Bartley was living in a sixth-floor apartment. The building’s elevator frequently broke, forcing Bartley to leave her wheelchair behind and walk up the stairs. Bartley, a survivor of childhood polio, can walk for short distances without her chair, but not without pain. After the elevator was out of order for a whole month, Bartley asked her landlord to move her to her current second-floor apartment.

Accessible units don’t always go to people with disabilities, especially lower-income individuals. “You have to have enough money and have proof of credit,” said Don Rickenbaugh, Queens director of a non-profit called the Center for Independence of the Disabled. “It doesn’t always work out, so able-bodied people get them.”/

A 2018 report conducted by The City of New York reports that “people with disabilities are more likely to be unemployed and living in poverty.” Across the country, 29.6 percent of people with disabilities (aged 18-64) lived below the poverty line in 2017, compared to 13.2 percent of people without disabilities.

The city and state offer programs like Access-to-Home, which helps people make alterations to non-accessible apartments, and Housing Connect, which helps people find accessible housing apartments, but the waitlists are long. “It may take years for them to contact you and say we have an apartment for you,” said Rickenbaugh.

Jacobs noted that the waitlists for accessible housing reflect a citywide crisis. “The problem is there’s just not enough affordable housing in New York City,” he said.

Wheelchair users who live in a non-accessible apartments are legally allowed to make modifications that will make kitchens safer and easier to use. Tenants are not legally bound to return apartments to their original state when they move out. Without modifications, using the kitchen is tricky.

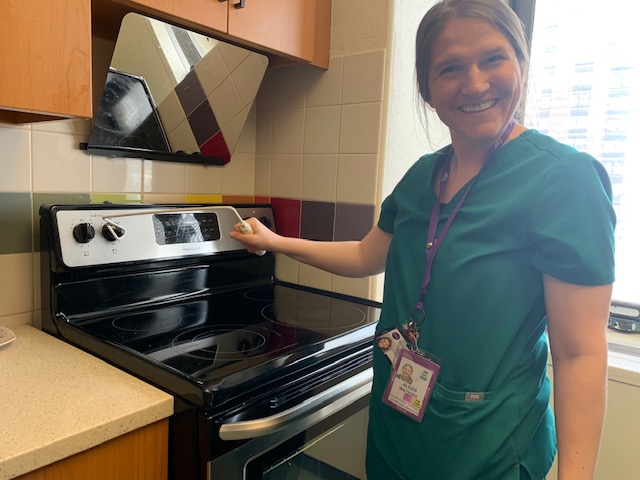

“I have to lift the pot off the stove to look at it,” Bartley said, “What if I take off this pot and the thing spills in my lap?” Many wheelchair users prep food – including slicing, dicing, and chopping- on cutting boards balanced on their laps because they can’t reach the countertops. Occupational therapists working with wheelchair users at Bellevue Hospital say reaching items in the kitchen is the number one challenge they hear from patients using wheelchairs.

Remodeling the kitchen for wheelchair accessibility can ease some of these challenges. Lowering countertops and sinks to wheelchair-height and replacing appliances with ones compliant with the guidelines set by the American Disabilities Act (ADA) are common modifications.

Fully remodeling a kitchen for wheelchair accessibility costs anywhere from $15,000-$20,000, according to the home remodeling guideline website Fixr. While tenants may have to cover some of the more extreme modifications – like new ADA-compliant appliances or new countertops – landlords are legally required to make “reasonable” modifications under the Fair Housing Act.

“Some landlords don’t like doing it, but it’s the law,” said Rickenbaugh, who explained that landlords only have to accommodate wheelchair users if it’s within their budget and reasonable ability. “Sometimes, their hands are tied. They really can’t move people around because they’re full or the money situation for the landlord is not so great,” he said.

Some tenants – especially those in rent-controlled or rent-stable apartments – worry about upsetting their landlords, and are afraid to request physical modifications to their kitchens. Depending on a wheelchair user’s condition and whether they live alone, there are some simpler solutions to kitchen-related challenges.

“It’s not always about physical changes, it’s about changing behaviors,” said Ain-Lian Lim, Director of Occupational Therapy at Bellevue. Such solutions include storing frequently-used items on countertops instead of in cabinets, lining trays with non-slip mats to prevent spills and buying inexpensive tools that help with things like reaching stove knobs.

After living in the NYC apartments for over a decade, Bartley’s started keeping most of her cooking supplies on her countertop and cooking her meals in a toaster oven instead of the full-sized oven to avoid having to reach inside from her chair. To chop up veggies for one of her favorite chicken or shrimp dishes, she uses the coffee table in the living room. If she needs something from a high cabinet, she waits until a family member or friend comes over for visit, and asks them to take it down.

“We have to develop ways and means of helping ourselves,” she said proudly.

Your Comments