Bronx gardens grow self-sufficiency plot by plot

Karen Washington helped create the Garden of Happiness, on 181st and Prospect Avenue in the Bronx, from a garbage-filled lot nearly 30 years ago. Photo: Xinyu Jing.

By Ilgin Yorulmaz

Karen Washington and Mike Young have been trying to start a Black & Decker trimmer in the community garden on Prospect Avenue, the Bronx. A tree fell during a ferocious blizzard in January, and has blocked one of the garden plots ever since.

But there is a bigger problem: The garden has no power outlet. Ever resourceful, Washington goes to her truck and produces a mobile generator and an extension cord so that Young, a local carpenter and fellow gardener, can get to work.

The 62-year-old Washington, a food activist farmer from the Bronx with blond dreadlocks and a huge smile, recently received the Earth Day Initiative Award at an event in Union Square. She says that she can’t rest until a problem is solved, especially if it’s as big as hunger.

Washington’s philosophy, “Food should be a right for all and not a privilege for some,” is the basis of her 30-year journey from life as a single mother with young children to the godmother of community gardening in the Bronx.

The one-time physical therapist started out with a plot in front of her house that had been left untouched by developers for years. “There was too much bedrock; they didn’t want it,” Washington says. With some help, she turned it into a garden. Her first harvest consisted of eggplants, peppers and collard greens, but it’s the smell of her first tomato that is locked in her memory: “I didn’t know it could smell so good. It got me hooked up.”

Since then, Washington’s been teaching people to grow their own fruit and vegetables, with the goal of creating easy access to healthy food, starting in people’s backyards.

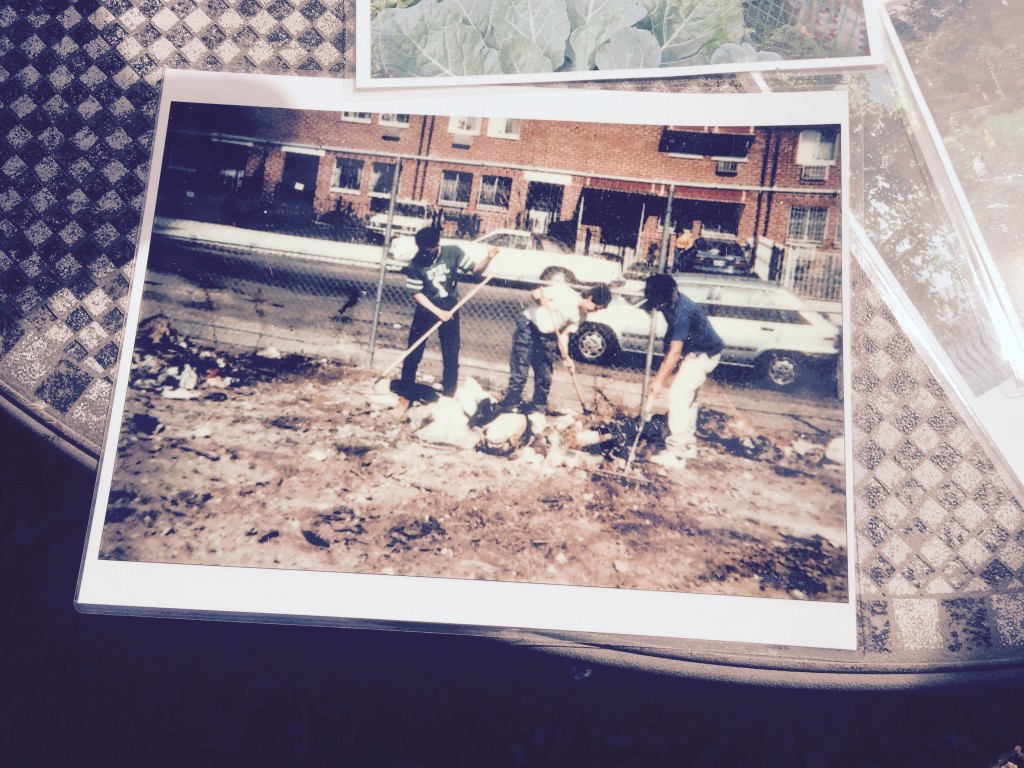

The Garden of Happiness, circa 1985. Photo: Karen Washington.

One in six people are food insecure in New York City, according to Hunger Report 2015 by Hunger Free America, a national movement working for access to nutritious food and an end to hunger. The highest rate is in the Bronx, where one in three people go hungry and are likely to rely heavily on small convenience stores that sell packaged, processed foods that are often high in sugar and fat.

Washington says she has recently spotted a newly-opened bodega on 182nd and Southern Boulevard and went in, curious to see what they stocked. “From a distance, I thought I saw vegetables on the shelves. But they were just crisps in green packages,” she says.

Bodegas usually don’t have refrigerated storage to stock fresh produce, and none of the local farmers markets operates in the Bronx during winter.

Washington’s solution involves using community gardens in two ways – to provide fresh produce for residents, and to enable them to sell their surplus at their own farmers markets.

Every day, it falls to one of the gardeners like Cheryl Holt to pick up freshly-laid eggs from the garden coop. Photo: Ilgin Yorulmaz.

A former president of New York City Community Garden Coalition, a 20-year-old advocacy group with members from New York City’s 530 community gardens, Washington has seen her Garden of Happiness in the Bronx grow into 36 plots. Each plot costs $35 a year and revenues go back to maintenance of the garden. Residents receive training and help from initiatives such as Just Food and New York Botanical Gardens’ GreenUp, both of which Washington represented as a board member in the past.

On a sunny Wednesday, a group of gardeners gathered to prepare their spring plantings.

Maria Molina, 50 and Juana Carino, 46, are both from Mexico and have large families. Molina is planting onions today. Carino is shoveling the earth vigorously to plant “a little bit of everything: tomatillos, zucchini, cilantro, green beans and cifiche (lima beans).”

Victoria Cabrera, 62, is from Honduras and takes care of chickens at the garden. They produce 4-6 eggs per day. Once liberated from their coop at the back, her nine “girls” strut through the grounds under the watchful eye of several cats.

While they work all year to maintain the garden, gardeners harvest produce only between June and October. Then they’ll have a big barbecue. “It brings community sense,” says Washington.

Gardeners prepare their lots for planting. Their choice of vegetables like tomatillos and jalapeño reflect the neighborhood’s Latin American roots. Photo: Xinyu Jing.

It depends on the family size, but gardeners like Carino usually have enough produce to sustain them in the warm months. She freezes and makes the leftover produce last until January, and buys only the foods, like avocado, that she can’t cultivate due to the cold New York weather. Until June, the community farmers have to find their fresh produce elsewhere. They shop for fruits and vegetables at local supermarkets in Tremont and Crotona. “A bit expensive, but that’s the only way,” comments Carino, who uses food stamps to supplement her family’s food needs.

Produce from four plots in the garden go to La Famiglia Verde Farmers’ Market, a coalition of five community gardens in the Bronx, set up in Tremont Park on Tuesdays from July to November. Each Happiness gardener donates any surplus produce from their own plots. “We go around and check prices at supermarkets and price our produce competitively,” Washington says. The market accepts SNAP benefits, or food stamps. Any money they make gets plowed back into the garden.

Although income inequality is the biggest issue in underserved neighborhoods’ hunger issues, unhealthy eating has deeper roots in people’s habits and lack of basic cooking skills. “A big gap exists between generations when it comes to being able to cook,” says Washington.

Despite a common assumption that there are more fast-food restaurants in minority neighborhoods, a 2014 article in The Atlantic cited a study by the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, which revealed that most of the 6,716 fast-food restaurants in their sample were located in majority-white neighborhoods. The restaurants located in minority neighborhoods were more likely to market to children, though, which contributes to higher rates of childhood obesity in the Bronx. That leads to the adult obesity Washington saw when she worked as a physical therapist. “Junk food is cheap and the food industry dumps it to these neighborhoods,” she says. She has a term for it: “food apartheid.”

In her work as a physical therapist, Washington saw clients suffering from food related ailments like Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. But they just wouldn’t give up eating fast food.

“When I started gardening, my clients were laughing at me, saying what a difficult job it was,” she remembers.

Today, plots are snapped up even before Memorial Day, the deadline to register for a plot in her garden.

Washington’s next initiative might be right on her doorstep: A domestic violence shelter for women and their children is being built next to the garden. “Those vulnerable parents and children need to be introduced to gardening and healthy food,” according to Cheryl Holt, 61, another gardener and physical education facilitator at DeWitt Clinton High School.

Gema Flores contributed to reporting of this article.

From left to right: garden members Victoria Cabrera, Pepe Rivera, Maria Molina, Juana Carino, and Guadelope Trendon. Photo: Ilgin Yorulmaz.

Tags: community garden, junk food, low-income, segragation, self-sufficiency

Your Comments