Issues: Defining gluten-free

Memorabilia sold at a local gluten-free bakery in the East Village. Photo: Brittany Robins.

When Maegan Perl, 26, attended a party last year at an Italian eatery in Brooklyn, she prepared herself for the all-too-familiar process of ordering her meal.

“I’m celiac, so if I eat anything with gluten or that has come into contact with it, I’ll get sick,” she said. The waiter assured her that he would take precautions and offered gluten-free pasta.

Perl, a coordinator at a fashion company, ate the dish and drove home, but felt nauseous and had to stop on the side of the road three times to vomit. By the time she reached her apartment, she grew weak and was rushed to the hospital—all this from a seemingly innocuous bowl of contaminated “gluten-free” pasta.

Gluten is a protein found in wheat, barley and rye. Approximately 3 million Americans have celiac disease, according to the FDA, which means that their body’s defense system reacts to gluten by attacking the lining of the small intestine. There are another 18 million Americans who define themselves as gluten-sensitive or gluten-intolerant, meaning that they tested negative for celiac but still experience gastrointestinal symptoms. Then there is the additional 30 percent of adults, who are gluten-free by choice, according to NPD Group, which tracks American diets.

Certified gluten-free flour sold at a local bakery in the East Village. Photo: Brittany Robins.

While gluten-free products appeared on the market in the 1980s, it was only in the last decade that the industry flourished. Today, 15 percent of North American households purchase gluten-free products, according to the Gluten-Free Agency, a market research company.

This surge in demand and sales is due to more households adopting a gluten-free diet in attempt to lead a “healthy” lifestyle, and to the increasing incidence of gluten-related illnesses—celiac is four times more common than it was 50 years ago.

Packaged Facts, another market research company, projected that the gluten-free industry in the United States will reach $5.5 billion by the end of 2015 and $6.6 billion by 2017. The industry has seen an annual growth rate of 34 percent in the last five years, according to the company’s research.

In August 2014, the FDA came out with label regulations, defining gluten-free as 20 parts per million of gluten, or less. Despite this, Cheryl Harris, founder of Harris Whole Health, and Mary Schluckebier, executive director of Celiac Support Association, agree that cross-contamination, confusing labeling and a lack of restaurant regulation present significant health risks to celiac sufferers.

“The community was glad to see something concrete,” said Cheryl Harris, referring to the parts per million limit. Harris, who in 2007 founded Harris Whole Health, a DC-based nutrition counseling service for celiac patients, counsels clients on symptoms, foods to avoid and tips for dining out. She observes a gluten-free regimen herself.

“The downside is that the FDA doesn’t regulate testing. They stopped short of saying that companies need to test and submit reports.” The reason, she said, is that it is too expensive for companies to test their products repeatedly.

Because there is no mandated testing, Tricia Thompson founded Gluten Free Watchdog in 2011, an organization that independently tests gluten levels in products labeled “gluten-free” and those that are inherently gluten-free. Consumers can send in requests for products to be tested, but items are generally selected at random by the organization, about 96 new products each year.

Thompson found that 32 percent of naturally gluten-free grains and flours contained gluten in amounts of 25 to 2,925 parts per million. These products ranged from a beverage and bread, to cookies, hot cereal, spices and tortilla chips. “There is no rhyme or reason to how categories of products test,” said Thompson.

On a more encouraging note, approximately 95 percent of the 158 labeled “gluten-free” free products tested contained less than 20 parts per million.

Gluten-free cupcakes served at Tu-Lu’s, a local bakery in the East Village that is certified gluten-free. Photo: Brittany Robins.

“The majority of manufacturers are getting it right,” said Thompson. She added that generally it’s the products that are inherently gluten-free, like millet, that pose more of a risk, because they are often produced and packaged in fields and facilities that are contiguous to other gluten-filled grains.

At a Starbucks in Chelsea, Perl expressed concern over the lack of mandated testing and Thompson’s findings. “I thought with the new regulations I wouldn’t need to be concerned anymore,” she said, nibbling on a frosted cupcake she hoisted from her purse.

But Talia Hassid endorses the regulations. Hassid is a spokesperson for Celiac Disease Foundation, a California-based non-profit that engages in funding, advocacy, education and research for the celiac community.

“Cross-contamination shouldn’t be an issue anymore, as long as the product is labeled ‘gluten-free,’ meaning that company has taken necessary precautions,” she said. She dismissed the cross-contamination findings as outdated, even though Thompson says that she tests eight new products each month and gets consistent results.

While the FDA claims that 20 parts per million is the level that people with celiac can tolerate without feeling sick, ingesting even small doses of gluten can cause damage to the intestines, according to Dr. Jennifer Bonheur, a Manhattan gastroenterologist. Bonheur said that individuals can be asymptomatic but still have internal damage from ingesting gluten, which can lead to detrimental long-term effects like anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, vitamin deficiencies, nervous system disorders, seizures, dementia and migraines. She added that there is an increased risk of intestinal cancer if someone with celiac continues to expose themselves to gluten.

Perl, who has had celiac disease for eight years, is cognizant of this danger. “Ingesting gluten without knowing it and not feeling symptoms is scary,” she said, “because you don’t know what’s going on inside you.”

There are also issues with confusing labels on gluten-free products that carry disclaimers about possibly containing traces of gluten, and with the ambiguity of rye and barley ingredients.

“I have to be careful with products labeled ‘gluten-free’ because sometimes in small writing it says ‘may have come into contact with wheat,’ and it’s easy to miss,” said Perl.

Harris acknowledged that while the labeling laws have made it easier for consumers to spot wheat in products, the lesser-known but equally dangerous barley or rye are not as clear.

“It’s not so easy to spot barley and rye, which are less common than wheat and often have confusing names,” said Harris. For instance, in certain soups, barley is used as a thickening agent but is sometimes labeled as its scientific name, “genus hordeum.” Rye, which is found in breads and crackers, is sometimes labeled as its scientific moniker, “genus secale.”

Gluten-free products are also more expensive than their gluten-containing counterparts. A study by Dalhousie Medical School in Canada compared prices of 56 gluten-filled products with gluten-free items. Gluten-free products were on average 242 percent more expensive than regular products.

A spread of gluten-free treats at a local bakery in the East Village. Photo: Brittany Robins.

While Perl has managed to stay afloat with the elevated pricing of gluten-free products, for some it can prove to be a substantial economic issue.

Harris tried to incorporate gluten-free products at food banks but was unsuccessful because of the products’ elevated cost.

“Just because you need to be at a food bank doesn’t mean you can eat gluten,” she said. “Most of the products that low-income families consume are not gluten-free friendly and that’s a public health issue.”

To make gluten-free products more accessible, larger food corporations like General Mills, which owns Pillsbury and Chex, have added gluten-free products with comparable prices to their gluten-filled counterparts. A box of regular wheat-filled Chex cereal costs $3.18, while the gluten-free version costs $3.28. The regular Pillsbury chocolate chip cookie dough roll is priced at $3.96, and the gluten-free version costs $3.98.

“Big companies do a good job with their production because they don’t want to get sued,” said Harris. “General Mills has a dedicated gluten-free facility for their rice Chex.” A spokesperson for General Mills corroborated this claim.

However, Mary Schluckebier, executive director of the Nebraska-based Celiac Support Association, which conducts research and education for the celiac community, believes that smaller, local companies have an easier time guaranteeing the quality of their gluten-free products.

Over the last few years, the East Village has become a repository of gluten-free establishments. On 10th street alone, two gluten-free bakeries, Tu-Lu’s Bakery and Jennifer’s Way, flank one another. Perl said she occasionally ventures to the area to sample their sweet confections.

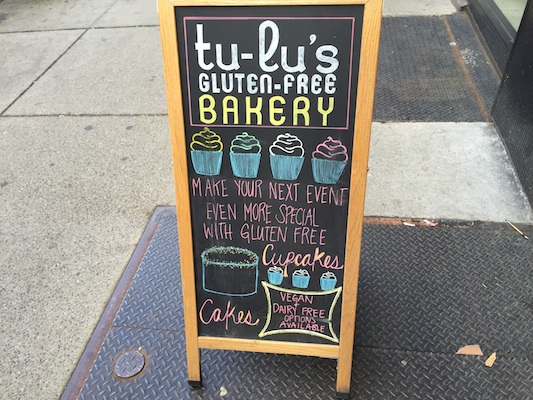

Signage outside Tu-Lu’s Bakery in the East Village. Photo: Brittany Robins.

Tu-Lu’s features a candy-colored décor and a wall mural of a cupcake tree sprawling toward a display of cookies, donuts and cupcakes. Jamie Rosenberg, the manager, said that the bakery, which opened five years ago, is one of the first and only bakeries in the neighborhood to be certified completely gluten-free by the Gluten-Free Certification Program. They use a mix of potato, rice and tapioca flour to create their goods.

The kitchen at Tu-Lu’s Bakery in the East Village is completely gluten-free. Photo: Brittany Robins.

“We get our products from the same sources to make sure there’s no cross-contamination. The suppliers know us, so if our regular brand isn’t in stock, they’ll send us another brand that’s certified gluten-free,” said Rosenberg. She added that the majority of their clientele is celiac or gluten-intolerant because customers are aware of the bakery’s dogged pursuit of purity, from production to packaging.

Just a few feet away at the rustic Jennifer’s Way Bakery, an intoxicating aroma of fresh baked goods wafts from the kitchen. Aprons that read, “Gluten can kiss my cupcake,” are sold in addition to desserts. The bakery is owned by television actress Jennifer Esposito, known for her work on shows like “Blue Bloods” and “Samantha Who?” She has celiac disease and claims that all items served at the bakery contain 10 parts per million of gluten or less and are produced in a gluten-free facility.

Jennifer’s Way, in the East Village, is not only completely gluten-free but also offers soy-free, dairy-free, refined sugar-free and egg-free options. Photo: Brittany Robins.

But dining at restaurants that are not solely gluten-free can present a danger for celiac sufferers.

Jessica Pearl, a New York-based nutritionist who specializes in celiac disease, said that many of her clients have given up eating out altogether to eliminate the risk. “It’s not the best solution, but it’s the safest for now,” she admitted.

Hassid said that restaurants lack control over production and preparation because they are not FDA-regulated.

“When restaurants have gluten-free menus, that doesn’t necessarily mean they have a dedicated kitchen or equipment, it just means they have gluten-free items on the menu. There is no guarantee there won’t be cross-contamination,” she said.

Larger companies like Pizza Hut, which began making gluten-free pizza in January 2015, pose a health risk, according to Schluckebier.

“Pizza Hut, where the flour is in the air and they’re making regular and gluten-free pizzas on the premises, have the most risk,” she said. Flour can linger in the air for 24 hours, which is perilous for celiac sufferers and gluten intolerants, according to the Gluten Intolerance Group of North America, a non-profit that promotes safe gluten-free practices for the food manufacturing and food service industries.

Representatives of Pizza Hut did not respond to requests for comment.

Despite the risk, many continue to eat out to avoid feeling isolated because of their dietary restrictions.

“The hardest thing is not being able to participate in certain things socially or not enjoying eating out as much,” said Perl. But since that day when she landed in the hospital from gobbling down a bowl of not-so-gluten-free pasta, she now packs a doggy bag of her own celiac-friendly noodles. “I just ask them to boil my pasta in a separate pot of water—at least I don’t feel left out.”

Your Comments