It was early in the afternoon, and the midday light was beginning to filter in, casting a fuzzy wedge of white over the plastic table cover. I was the last person left at the lunch table in my grandparents’ Shanghai apartment, which twenty minutes earlier had seated nine family members. Small heaps of crab shells were strewn in front of me.

My maternal grandmother was a phenomenal cook, but her simplest culinary offering has left the deepest imprint in my memory: hairy crabs, steamed plain, served with a dipping sauce of inky-black rice vinegar and slivers of ginger.

The crabs, native to freshwater bodies in East Asia, are named for their furry claws, and each fall, they take Shanghai by storm. These days, they are wildly expensive and widely desired — hairy crab dishes in fine-dining restaurants can cost up to $150, and live crabs from Yangcheng Lake, a lake known for producing the largest specimens, can sell for $20 apiece at fish markets. (Smaller crabs from less famous lakes cost around $5 each.) The crabs are prized for their gonads: rich orange roe in the females, and thick, creamy white milt in the males, which are slightly bigger. On a day trip I took to a neighboring city one year, live hairy crabs were given away on the bus as a raffle prize.

They were my mother’s favorite delicacy, and since we began my biennial fall visits to her mother six years ago, they’ve become mine too. Each trip, I accompanied my grandmother to the market, making our way through sun-dappled alleys lined with mahjong players and caged birds. The market was host to dozens of seafood vendors, but she always returned to the same one — a man with a lazy eye, surrounded by barrels of small, round crabs that shone like discs of muddied jade. I watched him as he expertly scrubbed and tied each crab, using his mouth to keep the straw taut. At the end of the transaction, my grandmother would hand him a few crisp 100 RMB bills emblazoned with Mao’s face. He threw in several small bottles of vinegar for free every time.

The three of us would dig in after lunch and dinner, after we’d already scarfed down bowls of rice and samplings of my grandmother’s other dishes: stir-fried lotus root, braised wood-ear mushroom and bamboo shoots, winter melon soup. When other family members were around, they were usually too impatient to partake in the messy, meticulous enterprise of extracting flesh from the crabs’ small bodies and thin legs. I was always the last person to finish, savoring each bite.

To eat a hairy crab, one must first flip it over to peel back its abdominal shell, and then remove the feathery lungs, hard stomach, and tiny, rubbery grey heart, which are believed to be toxic. Even if they aren’t, they taste bad. The crabs’ flesh, on the other hand, is sweet and delicate, and their roe is fatty and decadent. Superstition rooted in Chinese medicine says that crustaceans have a cooling effect on the body, which is why vinegar and ginger — “warming” ingredients — are crucial to achieve an optimal balance of yin and yang.

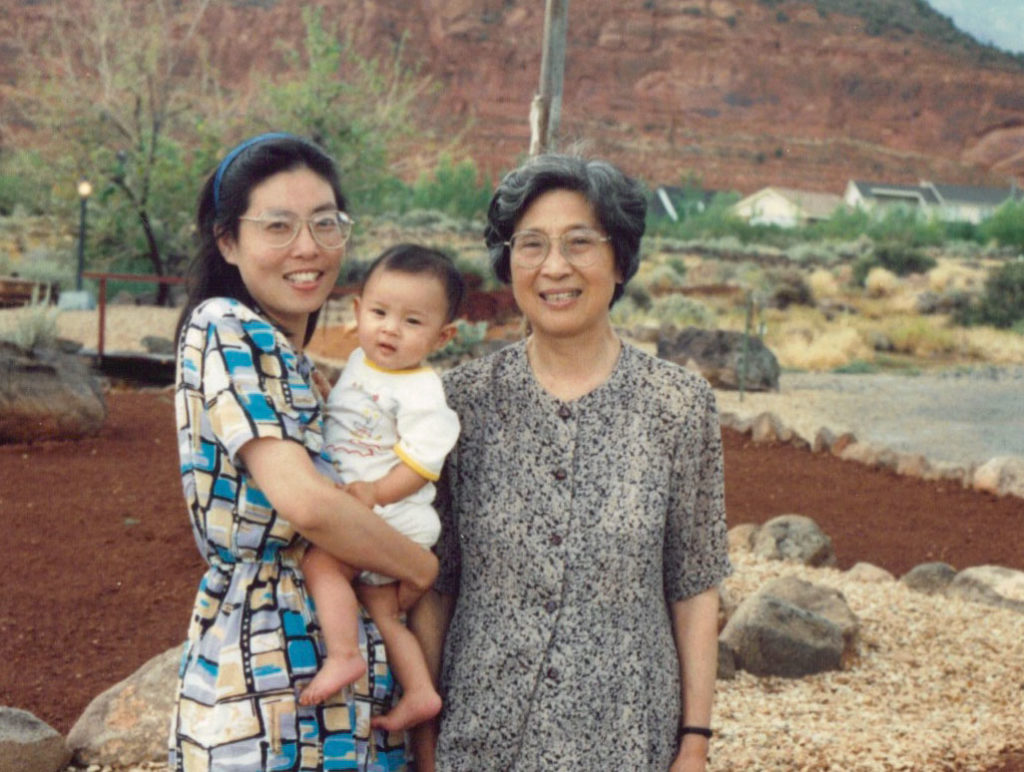

My last trip to Shanghai took place at the tail end of hairy crab season in 2017, when the crabs were at peak maturity. My mother was already there, helping my grandmother with errands around the city. Not longer after I arrived, the three of us walked to the market together. The sky was overcast, and on the way we stopped for egg-wrapped dumplings. My grandmother returned to the fishmonger with the lazy eye. Her gait was slower than it had been just two years earlier, but I wasn’t surprised: She was 91, after all. After lunch, I’d show her stretches to help with her aching back. Later, we would discover that the cause of the pain was late-stage pancreatic cancer.

The next time I step foot into Shanghai, my grandmother will no longer be there. I’ll stay in my grandparents’ now-vacant apartment, with its peeling wallpaper and humming lights, one last time before it’s tidied and sold. I’ll walk through the alleys listening to the gossip of the mahjong players and the twittering of the caged birds. When I find the fishmonger with the lazy eye, I’ll thank him. Then I’ll buy a bag of crabs.

Tags: China, Family, Seafood, Shanghai

Your Comments